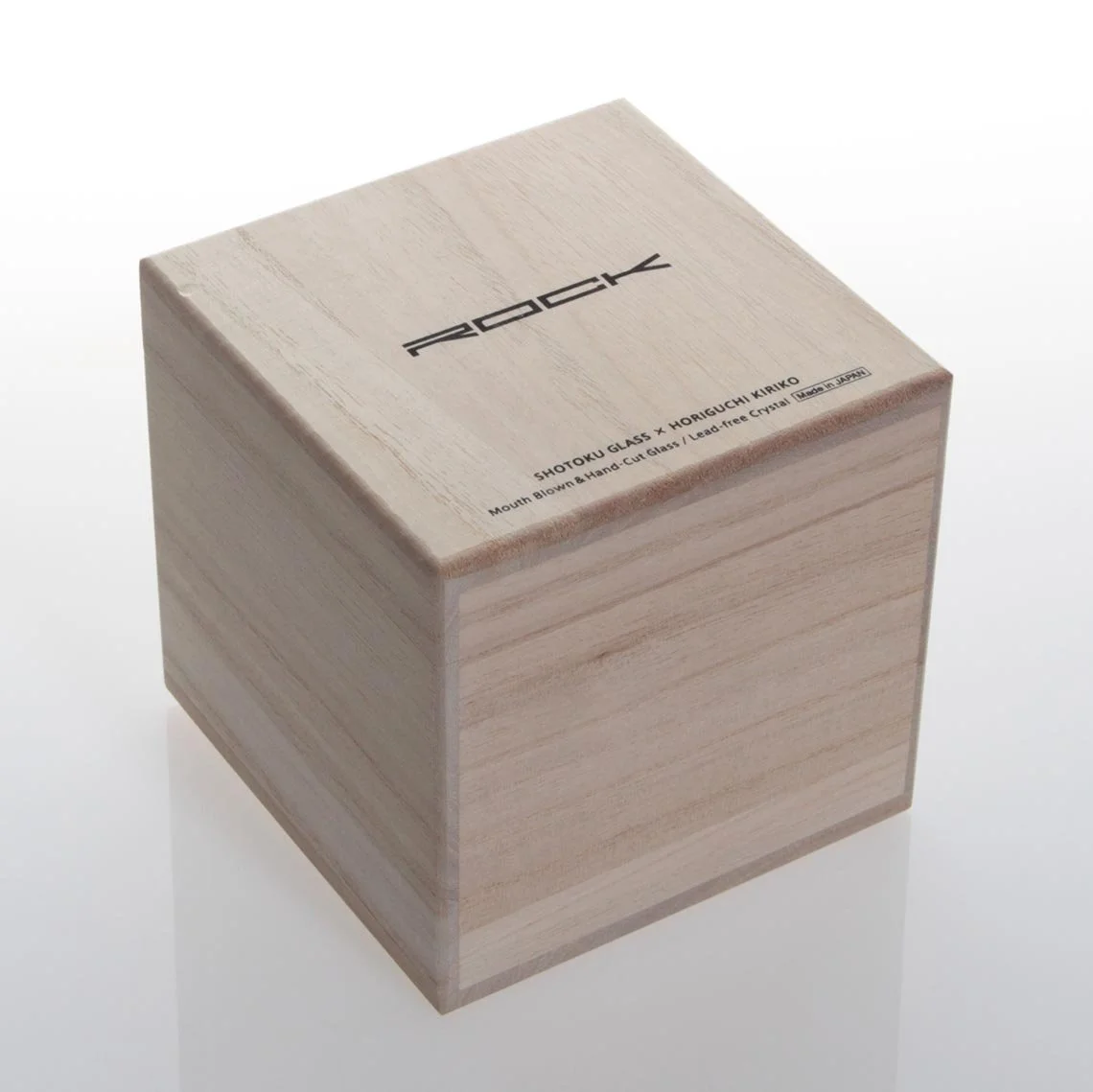

Kiribako: Where Practicality Becomes Beauty

In Japan, beauty is often inseparable from function. Objects are valued not only for how they look, but for how well they serve their purpose over time. Kiribako — boxes made from paulownia wood — are a clear expression of this philosophy. Designed first to protect, preserve, and endure, their understated appearance is a natural result of thoughtful material choice and skilled craftsmanship rather than decorative intent.

Used for centuries by artisans, collectors, and households alike, kiribako quietly demonstrates how practicality itself can become a form of beauty.

What Is Kiribako?

Kiribako (桐箱) refers to storage boxes crafted from kiri, or paulownia wood. Paulownia has long been prized in Japan for its unique physical properties: it is exceptionally light, naturally insect-resistant, fire-retardant, and highly effective at regulating humidity. These qualities make it ideal for safeguarding objects sensitive to temperature and moisture.

Because of this, kiribako has traditionally been used to store ceramics, lacquerware, tea ceremony utensils, textiles, scrolls, and other objects that require stable conditions to age well. The material itself performs the work — quietly protecting what is placed inside without the need for added technology.

Preservation, Provenance, and Trust

Beyond protection, kiribako plays an important role in documenting and preserving cultural value. Artisans, tea masters, and collectors often inscribe the inside lid with signatures, dates, or descriptive notes. In the world of traditional Japanese arts — particularly tea ceremony — the box can be as important as the object itself, serving as proof of origin and lineage.

For collectors, this inscription establishes trust. It connects the piece to its maker or school, and in many cases, directly affects its historical and monetary value. The box becomes part of the object’s story rather than a separate container.

Form Shaped by Use

Visually, kiribako is defined by restraint: pale wood grain, precise joinery, and an absence of surface ornament. This simplicity is not a stylistic choice, but the natural outcome of working with paulownia and prioritizing function.

The lid fits snugly but opens easily. The interior dimensions are tailored to the object it holds. Over time, the wood develops subtle marks and tonal shifts that reflect handling and age — not as flaws, but as evidence of continued use. In this way, kiribako aligns with a broader Japanese appreciation for objects that improve through care rather than replacement.

Craftsmanship Behind the Box

Making a kiribako requires patience and experience. Paulownia wood must be properly seasoned, sometimes over several years, to remove excess moisture and resin. Craftspeople then cut, laminate, and assemble the panels with precision so the box remains stable through seasonal changes.

Traditional techniques ensure a tight fit without metal fasteners, relying instead on wood movement and careful construction. Though visually simple, a well-made kiribako reflects deep technical knowledge — one that supports its contents for decades, often centuries.

An Enduring Standard

Today, kiribako continues to be used wherever care, presentation, and longevity matter — from traditional arts to thoughtfully packaged contemporary goods. Its continued relevance lies not in nostalgia, but in how well it fulfills its role.

By placing function at the center and allowing beauty to emerge naturally, kiribako offers a lasting example of Japanese craftsmanship — one where protection, respect, and thoughtful design are inseparable.